Under the glare of the midday sun, several dozen men wearing blue outfits, with shackles around their ankles, stood grouped together in a field of shrubs and tall grass.

One man among them, holding a long bamboo cane, started to shout at the thin-looking prisoners and they began to use hoes and spades to clear the thick vegetation. “One, two, three, four!” he yelled rhythmically, setting a quick pace for the work.

Nearby, a stocky prison warder was looking on with a rifle slung over his shoulder and an umbrella to shield him from the blazing sun.

The convicts were from KaungHmu Labour Camp and were seen in June as they cleared a piece of wasteland along the Mandalay-Lashio Road in Shan State for the expansion of a sugarcane plantation.

The man barking orders was a prisoner appointed to be a so-called prison management assistant, who acts as an enforcer and by doing so can avoid labour.

These men - also called “stick-holders” in Burmese - not only use violence to deal with dissent, former prisoners said, but also flog labourers into working harder.

“The stick-holders would beat us at will. We worked at the front and they beat us from the rear. Even if a tiny plant was left after clearing weeds in the sugarcane plantations we were beaten,” said Zeyar Lin, an ex-convict released from KaungHmu Labour Camp in early June.

Harsh working conditions and daily beatings are the norm in KaungHmu, he said. Those who just arrived in the camp, located in a mountain town called Naung Cho, suffered most. Prison officers would try to break new prisoners and force them to pay bribes to escape beatings and heavy labour.

“As soon as we entered the main gate, they slapped and kicked us. When I tried to raise my head a bit to be able to breathe, someone ran over and kicked me in the face,” said Zeyar Lin.

A months-long investigation by Myanmar Now into Myanmar’s prison labour system has revealed that thousands of convicts are likely suffering such abuses while they are forced to perform back-breaking manual labour on the orders of prison authorities.

In dozens of interviews, ex-prisoners and former prison officials said authorities employ such practices in many camps in order to exact bribes from prisoners, or to earn profits from their free labour.

The practices continue months after Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) came to power. Many NLD members themselves were political prisoners during their struggle against military rule, while Suu Kyi was kept under house arrest for some 15 years.

The sources also allege that prison authorities routinely put convicts at the disposal of private companies in return for payments - a practice that would violate international conventions against forced labour that Myanmar has signed.

However, the Ministry of Home Affairs indicated last week it would not launch an investigation into prison practices such as those uncovered by Myanmar Now, with a deputy minister telling parliament there had been “no legal violations in the prison system.”

A Ministry of Home Affairs spokesperson said the ministry would look into Myanmar Now’s findings but gave no comment ahead of publication of this report.

This is the first in a series of Myanmar Now reports, which will reveal how current and past practices in prison labour camps have resulted in abuses, corruption, exploitation, and the deaths of possibly thousands of convicts.

MILITARY RULE

Currently, there are 48 labour camps that hold an estimated 20,000 prisoners, according to the Correctional Department of the Ministry of Home Affairs. It officially refers to the sites as “manufacturing centres” and “agriculture and livestock breeding training careers centres”.

Classified government documents obtained by Myanmar Now show how former military governments, which held power for half a century after the army seized power in 1962, established the current prison labour system and its policies. Deaths were common in the camps in the past as prisoners performed hard labour without sufficient food or medical care, former prisoners and officials recalled. Only political prisoners were exempt from labour.

Food and care in the camps have improved since 2000 and general death rates in prison labor camps have fallen sharply to around 40 annually by 2014, according to government figures. But Myanmar’s recent democratic reforms have bypassed the prison labour system, this investigation has found, while widespread abuses persist and junta-era policies remain in place.

Human rights activists and others with knowledge of the system urged the government to introduce reforms urgently.

“Personally, I think the new government should work towards shutting down all these prison labour camps as a political priority,” said Khin Maung Myint, a former Chief Jailor who retired in 2002 after 25 years at the Correctional Department who has since become a legal consultant on Myanmar’s penal system.

“Prisoners at these camps are being punished in a way that violates existing laws,” he said, adding that prisoners receive inadequate food and healthcare while prison authorities “are trying to extract all their labour in all sorts of ways.”

BEATINGS, BRIBERY AND PRIVILEGES

Among the 48 labour camps, 30 sites are dubbed “agriculture and livestock breeding career training centres” where prisoners work on plantations run by the Correctional Department, or are put to work at private plantations and local farms.

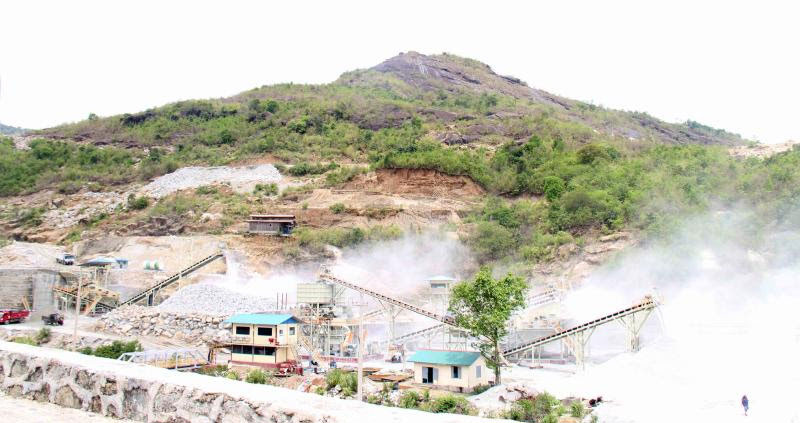

At 18 sites, located mostly in Mon States in southeastern Myanmar, thousands of convicts are deployed in rock quarries - officially called “manufacturing centres” - where they break granite and limestone boulders and crush them into gravel with sledgehammers.

The gravel is sold to government agencies or private companies for infrastructure and construction projects, while these sales bring in millions of dollars in revenues for prison authorities, according to production documents seen by Myanmar Now.

A Myanmar Now reporter made observations at nine prison labour camps in Shan and Mon states, and in Mandalay and Sagaing Region, and obtained photo and video evidence of harsh labour practices.

In interviews, ex-inmates from camps in Shan State’s Naung Cho Township and Sagaing Region’s Kalay Township consistently described being forced to pay bribes to avoid abuse and hard labour.

KaungHmu Labour Camp is one of five camps in the mountains around Naung Cho, at an altitude of around 1,000 metres where the nights are cold and the days are hot.

Some 200 men are held in KaungHmu and work six days a week on the camp’s 140-acre sugarcane plantation, or in private sugarcane- and corn-fields and rice paddies that dot the green, fertile valleys.

Zeyar Lin, 25, arrived at KaungHmu in early 2015; he was a former policeman from Bago Region who was serving a two-year sentence for fighting with his superintendent.

On his way to the camp, warders put iron shackles on his feet to prevent him from running away, he said, and upon arrival prison officers quickly began to increase pressure on him through beatings and a crushing workload.

“I was accused of being slow at work, so my back was beaten, my buttocks were beaten - at least 30 strokes every day,” he said. “I told the management once that I was sick and could not work. There and then, two prison officers beat me with their bamboo sticks.”

After a month, he realised his suffering would only stop if he bribed officials and his mother paid around US$500 to the camp’s Deputy Chief Jailor. He was then assigned to boil water and prepare tea or coffee for prison officials, a task he performed until his release.

‘WE WERE ALL SLAVES’

Zeyar Lin said the poorest prisoners had no such options, and some resorted to offering sex or other services to wealthy convicts or the “stick-holders” in order to seek protection.

“You will bribe to get a better task, you will sacrifice your body, or you will toil as an animal. You had no other options – we were all slaves,” he said.

Khin Maung Myint, the former Chief Jailor, said the prison labour system encourages abuse and corruption because it gives prison authorities full powers to assign convicts labour tasks and enforce corporal punishment.

“You can bribe officials for what kind of iron shackles you want to be put on: lighter ones or heavier ones,” he said. “Or you have to bribe more if you want to have the shackles taken off. Some who can’t afford it will have to wear them until they are released.”

According to current prison rules, an inmate cannot be kept shackled longer than two months after he has arrived at a camp.

Aung Soe, 51, served a total of 17 years in Myanmar’s prisons and was released from Hokho Labour Camp in Naung Cho in 2014.

“The reason why prisoners are beaten is to make everyone fear the prison staff. When prisoners lose all hope, they will bribe officials,” he said, adding that those who pay $1,000 might become a clerk, while someone who can raise $700 can become a “stick-holder”.

He said some convicts with money actually prefer labour camps to prisons, as they can bribe their way to privileges and enjoy the freedom to move around outdoors without being confined to a cell.

During a brief visit to a camp in Naung Cho, this reporter was able to exchange a few sentences with a prisoner convicted for murder. The man, 37, was lanky and his skin was darkened by daily toil in the field, which had been forced to do for the past year and a half, he said.

“I was beaten just yesterday,” he said pointing at scars on his legs. “If I could get 300,000 kyats (about $250), I can buy the position of water boiler (to escape labour), but none of my family members has ever visited me.”

“You can clear the weeds for one acre, then the next day you are asked to do two acres - I can’t stand it anymore,” he said with tears welling up in his eyes. “I try to control myself so that I don’t I fight back.”

FORCED LABOUR

According to current and former prison officials, authorities in charge of labour camps also have dealings with private sector companies to generate revenues for the camps. The practice comes from a Correctional Department directive stating that camps must generate enough funds to cover their running costs.

Rock quarries supply construction firms with thousands of tons of gravel per day. Agricultural camps sell the produce from state-owned plantations and hire out convicts to private plantations and local farms, officials and former inmates said.

Zaw Win, a Myanmar Human Rights Commission member and director-general of the Correctional Department from 2004 to 2012, said prison authorities of camps in Naung Cho had a joint venture agreement with Ngwe Ye Pale Sugarcane Factory, which obliged the camps to supply prison labour and government land for the company’s 800-acre sugarcane plantation.

Myanmar Now made several attempts to reach officials at the Ngwe Ye Pale Sugarcane Factory for comment, but received no response.

Zaw Win, who is tasked with investigating prison abuses for the government-appointed commission, defended the arrangement, saying: “This is just to make sure that prison department doesn’t have to worry about having a market for its agricultural products.”

Zeyar Lin, the former inmate, said prisoners were regularly deployed in the fields of Ngwe Ye Pale Sugarcane Factory. “The prison authorities charged the company 3,000 kyats per prisoner, they sent 100 prisoners per day, but we earned nothing,” he said.

Local officials and community leaders living near labour camps in Sagaing Region and Mon State also told Myanmar Now that prisoners were regularly hired by local farmers to work their fields.

The deals between prison authorities and companies put prisoners at the disposal of the companies, a practice that would violate the 1930 ILO Forced Labour Convention, which Myanmar signed and ratified in 1955.

The Convention’s Article 2 states that convicted prisoners can only work if it is “any work or services exacted from any person as a consequence of a conviction in a court law, provided that the said work or service is carried out under the supervision and control of a public authority, and the person is not hired to or placed at the disposal of private individuals, companies or associations.”

PiyamalPichaiwongse, Deputy Liaison Officer with the ILO’s Myanmar office, said she could not comment on whether forced labour was taking place in the Myanmar prison labour system, as there had been few complaints and little evidence of wrongdoing.

After being interviewed by Myanmar Now, Zeyar Lin, the former convict, contacted the ILO to complain about his prison treatment in Naung Cho Township.

PiyamalPichaiwongse said the organisation was looking into the case as a “forced labour complaint,” adding that Zeyar Lin’s prison conviction did not include hard labour.

AUTHORITIES PLAY DOWN ALLEGATIONS

Htay Lwin Tun, the current superintendent of Htone Bo Labour Camp in Mandalay, was previously in charge of the five camps in Naung Cho. He denied that beatings and bribery were commonplace in the camps, acknowledging only one reported case of violent conduct in 2014.

“Since the case did not lead to lethal injury, I just gave a verbal warning to the prison officer involved,” he said in an interview with Myanmar Now at Htone Bo Labour Camp.

Min Tun Soe, a deputy director of the Correctional Department, told Myanmar Now that severe abuses and extreme labour conditions were a thing of the past, and that the reforms initiated by the government of former President Thein Sein between 2011 and 2015 had improved conditions for prisoners.

“I don’t claim that the beatings have completely stopped, but general conditions regarding food and accommodation have improved,” he said, adding that beatings and bribery only occurred in isolated cases where prison management was corrupt.

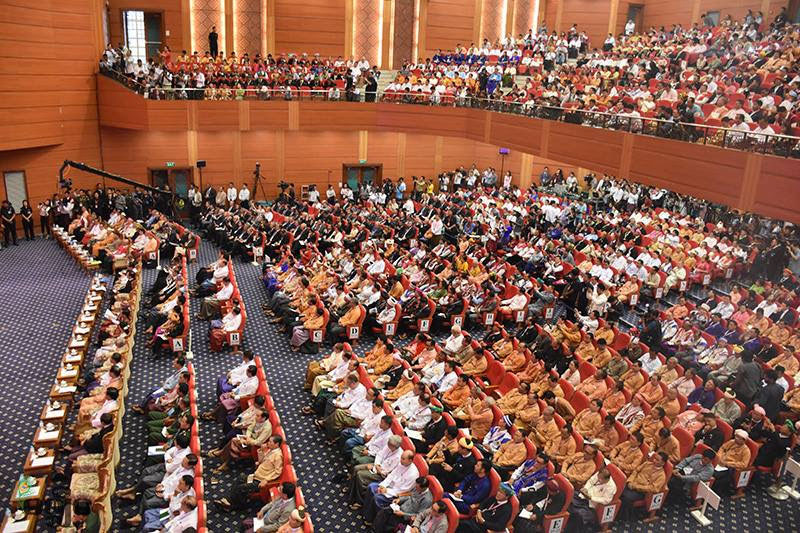

On Aug. 26, Lower House lawmaker Win Myint Aung, representing the NLD in Sagaing Region’s Depayin Township, asked the Ministry of Home Affairs, which remains under military control, whether the ministry would allow lawmakers to investigate prison conditions, including reports of corruption and abuses in labour camps.

Deputy Minister Gen. KyawSoe responded that the Correctional Department had effective mechanisms to investigate such complaints, adding that no violations had been reported. He said the Myanmar Human Rights Commission and the International Committee for the Red Cross were also monitoring prison conditions.

Zaw Win, the Myanmar Human Rights Commission member, insisted that violent abuse in labour camps was limited to isolated cases and was not an institutional problem.

“There is some scolding and slapping, but no more torture and cruel beatings like in the past,” said Zaw Win, whose commission is appointed by the President’s Office.

David Mathieson, a senior Myanmar researcher with Human Rights Watch, said government officials and the commission were turning a blind eye to abuse.

The Home Affairs Ministry should order a review of the prison labour system with the aim of ending it, he said, while the NLD-dominated parliament “should announce an immediate investigation into the Department of Corrections … that includes a thorough accounting of all the prisoners thought to have disappeared into abusive labour camps.”

A LACK OF REFORMS

Myanmar Now has obtained hundreds of internal Correctional Department documents that stretch back decades, and that shed a light on junta-era policies for managing the prison labour camps.

A document from Feb. 23, 1993, refers to a statement by then-Minister of Home Affairs Lt-Gen. Phone Myint who said prisoners’ labour was “wasted” if they only remained incarcerated. Their free labour should be used instead for state-owned plantations, infrastructure projects and to generate funds that cover running the prisons, it noted.

As late as October 2014, junta-era policy language was still in use by Thein Sein’s government to explain its prison labour policies.

Former Deputy Minister of Home Affairs Brig-Gen. KyawKyaw Tun told parliament at the time that the labour camps “use the prisoners’ labour, which is going waste in the prisons, for state-level agriculture, livestock breeding and rock quarries projects, and to ensure that the prisoners learn about agriculture and livestock breeding techniques and have attained a vocational profession upon their release.”

After the NLD assumed power in April, it urged all departments and ministries to formulate reform priorities for its first 100 days in office.

The Correctional Department’s reform plans for this period remained limited to a single sentence that read: “To increase the duration of family visits in prison from 15 minutes to 20 minutes, and allow family members to visit any day of the week.”